Table of contents

1. Labour Productivity, Q2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

UK Labour Productivity as measured by output per hour grew by 0.9% from the first to the second quarter of 2015 to the highest level ever recorded for this series, albeit some 15% below an extrapolation based on its pre-downturn trend

Output per hour in services grew strongly in Q2 to a record high, but manufacturing output per hour fell by 0.5% on the quarter, continuing the exceptionally weak trend for this series since the economic downturn

Whole economy unit labour costs grew 2.2% on the same quarter last year, the fastest rate since Q4 2012. This reflects an upward shift in the costs of labour as reflected in earnings growth and wider indicators

Following a review of 17 component industries within the Index of Services, we have changed the status of these series from Experimental to Official Statistics

2. About this release

This release reports labour productivity estimates for the second quarter (April to June) of 2015 for the whole economy and a range of sub-industries, together with selected estimates of unit labour costs. Labour productivity measures the amount of real (inflation-adjusted) economic output that is produced by a unit of labour input (measured in this release in terms of workers, jobs and hours worked) and is an important indicator of economic performance.

Labour costs make up around two-thirds of the overall cost of production of UK economic output. Unit labour costs are therefore a closely watched indicator of inflationary pressures in the economy.

Output statistics in this release are consistent with the latest Quarterly National Accounts published on 30 September 2015. Labour input measures are consistent with the latest Labour Market Statistics as described further in the 'General commentary' and 'Notes on sources' sections below.

New for this release are decompositions of movements in productivity which distinguish between ‘pure’ movements within component industries and an allocation component which captures the effect of shifts in resources between industries. In addition, seasonal adjustment parameters for hours worked in component industries have been reviewed, and we have introduced a small but important methodological change to benchmark the sum of seasonally adjusted hours worked across all industry components to the published total from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Further information is provided in an Information Note published by ONS in September 2015.

Back to table of contents3. Interpreting these statistics

Whole economy output (measured by gross value added - GVA) increased by 0.6% in the second quarter of 2015, while the Labour Force Survey (LFS) shows that the number of workers, jobs and hours fell by 0.2%, 0.1% and 0.2% respectively over this period. This combination of movements in outputs and labour inputs implies that labour productivity across the whole economy increased by approximately 0.9% in terms of output per worker and output per hour and 0.8% in terms of output per job.

Differences between growth of output per worker and output per job reflect changes in the ratio of jobs to workers. This ratio increased very slightly in Q2. Differences between these measures and output per hour reflect movements in average hours per job and per worker which, though typically not large from quarter to quarter, can be material over a period of time. For example, a shift towards part-time employment will tend to reduce average hours. For this reason, output per hour is a more comprehensive indicator of labour productivity and is the main focus of the commentary in this release.

Labour Productivity equation

This equation explains how Labour Productivity is calculated and how it can be derived using growth rates for GVA and labour inputs.

Unit labour costs (ULCs) reflect the full labour costs, including social security and employers’ pension contributions, incurred in the production of a unit of economic output, while unit wage costs (UWCs) are a narrower measure, excluding non-wage labour costs. Growth of ULCs can be decomposed as:

ULC equation

This equation explains how ULCs are calculated and how it can be derived from growth of labour costs per unit of labour (such as labour costs per hour worked) and growth of labour productivity.

In the first quarter, whole economy output per hour grew by 0.9% and ULCs grew by 0.5%. Plugging these values into the ULC equation and re-arranging yields an implied increase of approximately 1.4% in labour costs per hour. This implied movement differs from other ONS information on labour remuneration such as Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) and Indices of Labour Costs per Hour (ILCH), chiefly because the labour cost component includes estimated remuneration of self- employed labour, which is not included in AWE and ILCH.

Following a review of 17 component industries within the Index of Services, we have changed the status of these series from Experimental to Official Statistics. For further information, see ‘Improvements to the output approach to measure UK GDP, 2015’ published on 30 September 2015. Accordingly, we have also changed the status of output per job and output per hour estimates that use these series as numerators. This means that none of the series in this release are Experimental Statistics.

Back to table of contents4. General commentary

Productivity estimates in this release are derived from estimates of output of goods and services and of labour inputs – measured in terms of workers, jobs and hours worked. In general, output and labour inputs are measured independently of one another, with productivity calculated accordingly as the ratio of the two, although there are some activities where, in the absence of direct measures of output, labour inputs are used as a proxy, with productivity either assumed to be unchanged over time (as in public administration and defence) or assumed to move in line with the productivity trend in a measurable equivalent activity (as in a few small components of the index of services).

Whether measured by workers, jobs or hours worked, aggregate labour input fell slightly in the Q2 (April-June) quarter compared with Q1. Following the extraordinary strength of labour inputs over the last 3 years, this was the first quarterly decline in labour input since Q1 2013 for workers and jobs and the first quarterly decline in hours since Q2 2011. In terms of jobs, the decline was a little more pronounced in the production industries rather than in services, while in terms of hours worked, the reverse was the case.

On the other hand, the rate of output growth increased in Q2 after slowing in Q1. Aggregate output has now grown for 10 consecutive quarters and at an average annual rate of 2.8%. Much of the growth in output is accounted for by services, and particularly non-financial, non-government services.

Revisions to GVA flowing from the annual National Accounts benchmarking process do not significantly change the evolution of output. Growth of aggregate GVA (which can vary slightly from GDP) has been revised up in each of 2011 (+0.2%), 2012 (+0.3%) and 2013 (+0.7%), and revised down by 0.1% in 2014. These revisions broadly reflect revisions to growth of output of services. Growth of the production industries has been revised down a little in 2012 and 2013.

There are no material revisions to jobs estimates in this edition. Estimates of hours worked have been revised to reflect re-estimation of seasonal adjustment parameters and benchmarking of aggregate hours worked to the published LFS total. See ’New development in ONS labour productivity estimates’ published on 10 September 2015 for further information. Together with the revisions to GVA noted above, the effect is revised estimates of output per hour for all time periods and all component industries. For example, at the whole economy level, growth of output per hour has been revised from -0.3% to +0.9% in 2013. See the Revisions section below for more information.

Whole economy output per hour was the highest ever recorded in Q2, albeit only fractionally higher than Q4 2011 or Q2 2008, and some 15% below an extrapolation based on the trend prior to the economic downturn. Output per hour in services was also the highest on record, and about 2% higher than its pre-downturn level.

By contrast, output per hour for the market sector was approximately 2% below its pre-downturn peak level in Q2, implying that productivity in the non-market sector (not currently available because we do not produce estimates for non-market sector GVA) must be at a record high.

This is not the case for public administration and defence, education and healthcare services (industries O, P, and Q), where productivity on an output per hour basis was about 3% below its pre-downturn peak level in Q2. Although these industries are conventionally described as ‘government services’ they include market components (private education and healthcare), and there are elements of non-market activity in other industries besides O,P and Q, such as transport services and waste management.

One illustration of the difference between O, P, and Q and the non-market sector is provided by the differential movement in hours worked. Between Q1 2008 and Q2 2015 hours worked in industries O, P, and Q are estimated to have increased by 9.2%, whereas hours worked in the non-market sector (defined simply as total hours less market sector hours) are estimated to have decreased by 3.8%. Public sector employment across industries O, P, and Q fell more than this on a full time equivalent basis. This implies strong growth in labour inputs into the market sector components of industries O, P, and Q.

Figure 1: Cumulative contributions to quarter on quarter growth of whole economy output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- ABDE refers to Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (section A), Mining and Quarrying (section B), Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning Supply (section D) and Water Supply, Sewerage, Waste Management and Remediation Activities (section E)

- Allocation represents the contribution to the total change in output per hour due to movements in resources between industries, reflecting differences in productivity levels and movements in relative prices. For further information see ‘New developments in ONS labour productivity estimates’

Download this chart Figure 1: Cumulative contributions to quarter on quarter growth of whole economy output per hour

Image .csv .xlsFigure 1 provides a high level summary of movements in output per hour since Q1 2008 in terms of cumulative quarterly changes. Whole economy output per hour fell sharply in 2008 before staging a recovery up to mid 2011. Productivity then fell again through the second half of 2011 and through 2012, initially reflecting sluggish output growth and then reflecting strong growth in hours worked. Output per hour has grown by about 2.4 percentage points since Q4 2012, albeit with a period of flat productivity between Q3 2013 and Q2 2014.

Over the period since Q1 2008, movements in whole economy output per hour have been dominated by positive contributions from other services (that is, excluding financial services) and negative contributions from industries ABDE (non-manufacturing production and agriculture). Focussing on the period since the mini-trough in Q4 2012, the net contribution of ABDE has been close to zero. The combined contributions of the remaining industries has been to add about 3 percentage points to productivity, and there has been a negative contribution of about 0.6 percentage points due to shifts in resources from relatively high productivity industries to industries with lower productivity.

In this case, the negative allocation effect partly represents the impact of lower oil prices, which reduces the value of output of ABDE relative to other industries, and partly reflects a reduction in the share of manufacturing in total output.

Figure 2: Whole economy year on year changes to unit labour costs

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Labour cost per hour estimates in Figure 2 differ from estimates published in the Index of Labour Costs per Hour (ILCH) ONS release. The main conceptual difference is that ILCH measures costs of employees only, whereas Figure 2 includes labour costs of the self employed

Download this chart Figure 2: Whole economy year on year changes to unit labour costs

Image .csv .xlsFigure 2 shows annual changes in ULCs since Q1 2008, with the bars representing the decomposition of ULC changes into changes in labour costs per hour and changes in output per hour. The latter have been reversed in sign, so a negative bar represents positive productivity growth.

Negative contributions to ULC growth from generally positive productivity growth since the end of 2012 were initially accompanied by low or negative contributions from growth in labour costs per hour, allowing ULC growth to fall to -2.1% in Q2 2014. Since then, however, growth of labour costs per hour has accelerated, reaching 3.5% on the definition used in Figure 2 in Q2, the fastest rate since Q1 2010. This upward trend is also apparent in the Index of Labour Costs per Hour, which shows labour costs per hour excluding bonuses and arrears growing at 3.4% in the year to Q2, and also, although to a lesser extent, in average weekly earnings growth.

Analysis of ULC growth by industry (available in this reference table (267 Kb Excel sheet)) shows that the upward trend over the recent period is fairly broad based. One noteworthy feature of the industry breakdown is that ULCs in manufacturing are growing faster (3.1% in the year to Q2) than in services (2.1% over the same period). This has been the pattern since the economic downturn, but it contrasts sharply with the pattern between 1997 and 2007, when ULC growth in services averaged around 3% per year, compared with only 0.4% per year for ULC growth in manufacturing.

Back to table of contents5. Whole economy labour productivity measures

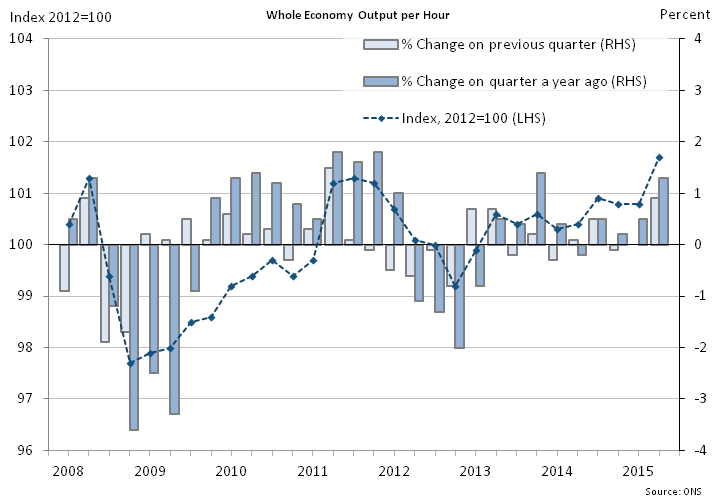

Output per hour continued on an upward trend that began in late 2012. The measure grew by more than 1% on the quarter a year ago and on the quarter it saw the largest rise since Q2 2011 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Whole economy output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 3: Whole economy output per hour

.png (35.4 kB) .xls (135.7 kB)Output per hour growth in the latest quarter was primarily driven by an increase in GVA, though it was aided by a slight fall in hours. Figure 4 shows that hours worked grew slightly faster than jobs from the start of 2011, suggesting average hours per job has increased. The difference between these two growth rates has narrowed more recently.

Figure 4: Whole economy labour productivity components

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: Whole economy labour productivity components

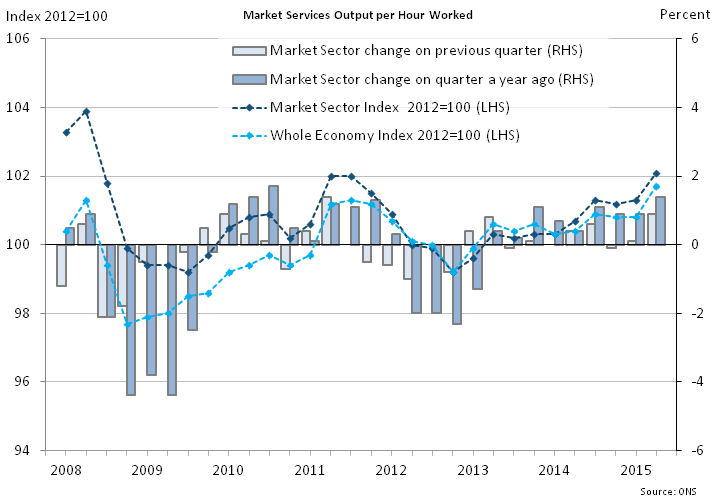

Image .csv .xlsEstimates for Market Sector output per worker growth have increased slightly faster than output per hour growth over recent years. This suggests that workers have been putting in more hours in the Market Sector, which excludes general government and Non-Profit Institutions Serving Households (NPISH).

In general terms, Market Sector output per hour growth continues to track that of the whole economy after the two measured converged following the financial crisis (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Market sector output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: Market sector output per hour

.png (40.8 kB) .xls (136.7 kB)6. Manufacturing labour productivity measures

Figure 6 shows output per hour in manufacturing in terms of annual changes and decomposed into broad component industries. Here the allocation element captures the effect of changes in output shares and relative prices within manufacturing. Prior to the economic downturn, most component industries made positive contributions to manufacturing productivity in most years. Since 2011, however, the picture has become more variable. A notable feature of Figure 6 is that the downturn in manufacturing output per hour on 2012 and 2013 was deeper than during the downturn in 2008 and 2009. Manufacturing output growth was negative in 2012 and 2013 but only marginally so. The weakness of manufacturing productivity in this period chiefly reflects remarkably strong manufacturing employment and hours worked.

Figure 6: Contributions to growth of manufacturing output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, annual 1998 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- CA-CD + CM refers to Food products, beverages and tobacco (CA), Textiles, wearing apparel & leather (CB), Wood & paper products & printing (CC) and Coke & refined petroleum products (CD). CM refers to Other Manufacturing

- CE,CF refers to Chemical and Pharmaceutical products

- CG,CH refers to Rubber, plastics & other non-metallic minerals (CG), Basic metals and metal products (CH)

- CI-CL refers to Computer products, Electrical equipment (CI,CJ), Machinery & equipment (CK) and Transport equipment (CL)

Download this chart Figure 6: Contributions to growth of manufacturing output per hour

Image .csv .xlsWhen manufacturing hours worked and jobs are separated from GVA, it is clear that both have flattened out from a strong downward trend in 2008 (see figure 7). Meanwhile, GVA estimates continue to bounce within a narrow range.

Figure 7: Components of manufacturing productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 7: Components of manufacturing productivity measures

Image .csv .xlsMore information on the labour productivity of sub-divisions of manufacturing is available in Reference Table LPROD01 (352.5 Kb Excel sheet) (Tables 3 and 4), and in the tables at the end of the pdf version of this statistical bulletin. Care should be taken in interpreting quarter on quarter movements in productivity estimates for individual sub-divisions, as small sample sizes of the source data can cause volatility.

Tables 3 and 4 include annual estimates for the level of productivity in £ terms for the National Accounts base year of 2012. These are estimates of GVA per unit of labour input and are not necessarily related to pay rates. Output per job (Table 3) varied from £44.1k in Textiles and leather (divisions 13-15) to £135.9k in Chemicals and pharmaceuticals (divisions 20-21). The average for the whole of manufacturing was £59.7k and the average for the whole economy was £48.2k in 2012.

Chemicals and pharmaceuticals was also top of the distribution for output per hour in 2012 (£73.2), with Basic metals and metal products (divisions 24-24) at the bottom of the distribution (£25.0). On this basis the average for manufacturing as a whole was £32.4 and the average for the whole economy was £30.2 per hour.

Back to table of contents7. Services labour productivity measures

Figure 8 provides a decomposition of growth of output per hour in services. Here the pattern since 2011 has also been weak by pre-downturn standards, though less so than in manufacturing. One noteworthy feature of this representation of the data is the comparatively large positive allocation components over 2005-2007, reflecting shifts towards high productivity components such as real estate and financial services.

Figure 8: Contributions to growth of services output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, annual 1998 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- G-I refers to Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (G), Transportation and storage (H) and Accommodation and food service activities (I)

- J refers to Information and communication

- K refers to Financial and insurance activities

- L refers to Real Estate activities

- M-N refers to Professional, scientific and technical activities (M), Administrative and support service activities (N)

- O-Q refers to Government Services

- R-U refers to Other Services

Download this chart Figure 8: Contributions to growth of services output per hour

Image .csv .xlsOverall, output per hour growth in services is now on a steady upward trend after a couple of periods of moving sideways between Q1 2009 and Q1 2011, then again Q3 2011 and Q2 2012.

The components of services output per hour are all on a strong upward growth trend (see Figure 9), although more recent data for hours and jobs are less robust. This slow down in hours and job growth, coupled with the positive GVA estimate, have driven the rise in output per hour for services in Q1.

Figure 9: Components of services productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to quarter 2 (Apr to Jun) 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 9: Components of services productivity measures

Image .csv .xlsMore information on labour productivity of services industries is available in Tables 5 and 6 of Reference Table LPROD01 (352.5 Kb Excel sheet) and in the tables at the end of the PDF version of this statistical bulletin.

In general, the dispersion of labour productivity growth rates across service industries is less pronounced than within manufacturing. But the dispersion of productivity levels is more pronounced. Yet, it should be borne in mind that labour productivity in industry L (Real estate) is affected by the National Accounts concept of output from owner-occupied housing, which adds to the numerator but without a corresponding component in the denominator.

Excluding industry L, output per job in 2012 varied from £20.9k in Accommodation & food services (section I) to £100.3k in Finance & insurance (section K). These industries were also at the bottom and top of the productivity distribution in terms of output per hour (Table 6).

Back to table of contents8. Revisions

There are revisions to UK productivity estimates in this release due to the publication on 30 September 2015 of revised National Accounts estimates consistent with the UK National Accounts Blue Book Book 2015 which will be published on 31 October 2015. An article summarising the effects of methodological, classification and other changes implemented in the latest estimates was also published on 30 September 2015.

The effects of the changes in Blue Book 2015 have broadly increased GVA since 1997, though the increase is relatively modest and much smaller than the impact of changes in Blue Book 2014. The largest upward revisions come from extending the coverage of incomes accruing to small businesses and from newly available survey data from the Annual Business Survey and the International Trade in Services Survey, among others.

Output in recent years in the services sector has benefited from the upward revisions to the National Accounts, while the production sector has seen slight downward revisions over the same period.

In contrast to GVA data, there are few revisions to employment data from the Q1 edition of Labour Productivity. However, following feedback from users we revisited the seasonal adjustment review of productivity hours, conducted prior to the last release. Details of the second review are available from the information note published in September.

The additional review has resulted in hours data that are less volatile than those published in the previous release. This is partly due to a shift in the seasonal adjustment methodology, though we have also benchmarked hours data to Total Actual Weekly Hours Worked data from the Labour Force Survey.

Because shifts in GVA estimates tend to dominate changes to short term labour productivity, the effects of the revisions noted above have led to a larger upward shift in recent output per hour data for services than for production. The upward revision is notable in the finance, insurance and other business services industry, where output per hour is on average 0.9% higher since Q1 2008 following revisions from Blue Book 2015 and changes to hours data. Productivity has grown in this industry despite the corrections to insurance data noted above.

Blue Book 2015 changes have also led to revisions to estimates of Compensation of Employees (COE) which affects estimates of unit labour costs. Growth of COE has been revised down by 0.3%, 0.4% and 0.9% in 2012, 2013 and 2014, respectively. Over a longer time span, the impact of Blue Book 15 on COE is much more modest.

Whole economy ULC growth has been revised downwards by 1.2% in 2013 and 1.0% in 2014. The downward revision in 2013 mainly reflects the large downward revision in growth of output per hour, while the 2014 revision is mainly due to the downward revision to COE growth.

Table A below summarises differences between first published estimates for each of the statistics in the first column with the estimates for the same statistics published three years later. This summary is based on five years of data, that is, for first estimates of quarters between Q3 2007 and Q2 20121, which is the last quarter for which a three-year revision history is available. The averages of these differences with and without regard to sign are shown in the right hand columns of the table. These can be compared with the estimated values in the latest quarter (Q2 2015) shown in the second column. Additional information on revisions to these and other statistics published in this release is available in the Revisions Triangles (2.46 Mb Excel sheet) component of this release.

Table A: Revisions analysis

| Whole economy | |||

| Revisions between first publication and estimates five years later (2007 Q3 - 2012 Q2) | |||

| Change on quarter a year ago | Value in latest period (per cent) | Average over 5 years (bias) | Average over 5 years without regard to sign (average absolute revision) |

| Output per worker | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Output per job | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Output per hour | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Unit labour costs | 2.2 | -0.2 | 1.3 |

| Unit wage costs | 1.9 | -0.4 | 1.3 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||

Download this table Table A: Revisions analysis

.xls (25.1 kB)This revisions analysis shows that whole economy labour productivity growth estimates have tended to be revised up very slightly over time (on a year-on-year basis). Growth of unit labour costs and unit wage costs has tended to be revised downwards. Were the average revisions to apply to the current release, growth of output per hour in the year to the second quarter of 2015 would be revised from 1.3% to 1.4% over the next three years. Growth of unit labour costs would be revised from 2.2% to 2.0%, while growth of unit wage costs would be revised from 1.9% to 1.5% over the same period.

A research note, ‘sources of revisions to labour productivity estimates’ (145.4 Kb Pdf) is available on the ONS website.

Back to table of contents9. Notes on sources

The measure of output used in these statistics is the chain volume (real) measure of Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices, with the exception of the regional analysis in Table 9, where the output measure is nominal GVA (NGVA). These measures differ because NGVA is not adjusted to account for price changes; this means that if prices were to rise more quickly in one region than the others, then this would be reflected in apparent improved measured productivity performance in that region relative to the others. At the whole economy level, real GVA is balanced to other estimates of economic activity, primarily from the expenditure approach. Below the whole economy level, real GVA is generally estimated by deflating measures of turnover; these estimates are not balanced through the supply-use framework and the deflation method is likely to produce biased estimates. This should be borne in mind in interpreting labour productivity estimates below the whole economy level.

Labour input measures used in this bulletin are known as 'productivity jobs' and 'productivity hours'. Productivity jobs differ from the workforce jobs (WFJ) estimates published in Table 6 of the ONS Labour Market Statistics Bulletin, in three ways:

To achieve consistency with the measurement of GVA, the employee component of productivity jobs is derived on a reporting unit (RU) basis, whereas the employee component of the WFJ estimates is on a local unit (LU) basis. This is explained further below

Productivity jobs are scaled so industries sum to total LFS jobs. Note that this constraint is applied in non-seasonally adjusted terms. The nature of the seasonal adjustment process means that the sum of seasonally adjusted productivity jobs and hours by industry can differ slightly from the seasonally adjusted LFS totals

Productivity jobs are calendar quarter average estimates whereas WFJ estimates are provided for the last month of each quarter

Productivity hours are derived by multiplying employee and self-employed jobs at an industry level (before seasonal adjustment) by average actual hours worked from the LFS at an industry level. Results are scaled so industries sum to total unadjusted LFS hours, and then seasonally adjusted.

Industry estimates of average hours derived in this process differ from published estimates (found in Table HOUR03 in the Labour Market Statistics release) as the HOUR03 estimates are calculated by allocating all hours worked to the industry of main employment, whereas the productivity hours system takes account of hours worked in first and second jobs by industry.

Whole economy unit labour costs are calculated as the ratio of total labour costs (that is, the product of labour input and costs per unit of labour) to GVA. Further detail on the methodology can be found in Revised methodology for unit wage costs and unit labour costs: explanation and impact.

Manufacturing unit wage costs are calculated as the ratio of manufacturing average weekly earnings (AWE) to manufacturing output per filled job. On 28 November 2012 ONS published Productivity Measures: Sectional Unit Labour Costs describing new measures of unit labour costs below the whole economy level, and proposing to replace the currently published series for manufacturing unit wage costs with a broader and more consistent measure of unit labour costs.

What is a reporting unit?

The term 'enterprise' is used by ONS to describe the structure of a company. Individual workplaces are known as 'local units' and a group of local units under common ownership is called the 'enterprise'. In ONS business surveys, reporting units are the parts of enterprises that return data to ONS. While the majority of reporting units and enterprises are the same, larger enterprises have been split into reporting units to make the reporting easier.

For most business surveys run by ONS, forms are sent to the reporting unit rather than local units, in other words, to the head office rather than individual workplaces. This enables ONS to gather information on a greater proportion of total business activity than would be possible by sending forms to a selection of local units. But it has the disadvantage that it is difficult to make regional estimates – for instance all the employment of, say, a chain of shops would be reported as being concentrated at the site of the head office.

Further differences between reporting unit and local unit data can be seen in the industry coding. Take, for example, a reporting unit with three cake shops and one bakery, each employing five people. The local unit analysis would put 15 employees in the retail industry and five employees in the manufacturing industry. But the reporting unit series puts all 20 people into the industry with the majority activity, in this case, retailing. Detailed industry figures compiled using the local unit approach will therefore be different from industry figures using the reporting unit approach, although the totals will be the same at the whole economy level.

Back to table of contents