The digital economy has transformed the way we do business. However it presents many challenges when it comes to measuring its performance and any change in the behaviour of consumers.

How do we measure the success of the economy in a rapidly changing world?

ONS Fellow and Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester, Diane Coyle discusses those challenges...

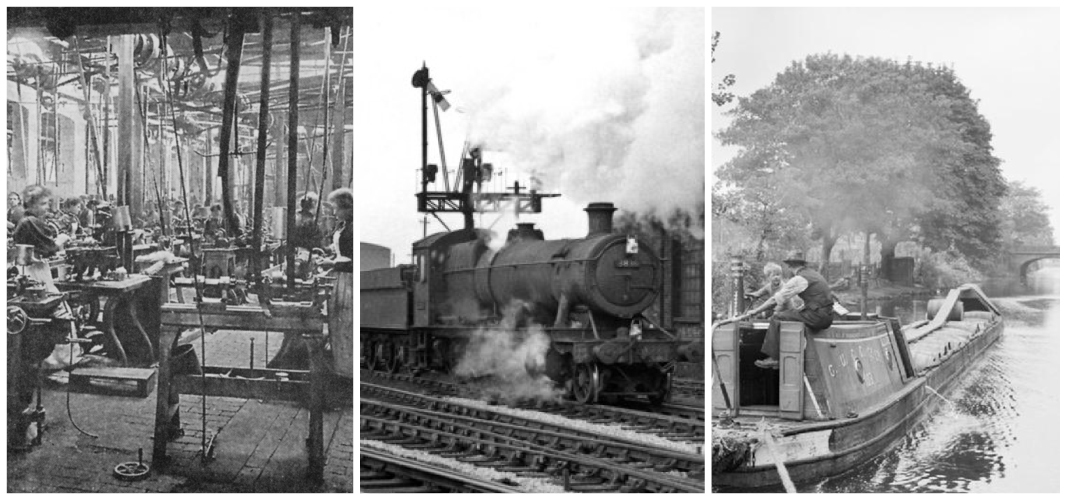

Thinking about Britain’s economy in the late 19th century calls to mind images of grimy cotton mills, mines, canals and railways.

Yet in an official Abstract of Statistics, published in 1886, only a dozen out of nearly 200 pages have any information about these symbols of industrialisation. The rest reflect the country’s economic past, dominated by agricultural production and trade.

Statistics are bound to lag behind what is happening in the economy when it is changing so rapidly. Statisticians now face a similar challenge to their Victorian forbears because of the effects of digital technologies.

In fact, there are many challenges. Some are more straightforward to deal with. The collection of data needs to cover new businesses, especially if they are growing quickly, and if they lead to different patterns of behaviour. Ensuring online retail sales (now more than 15% of the total excluding petrol) are included in the figures would be one example.

Internet Retail Sales (non-seasonally adjusted), UK, January 2007 to January 2016

Embed code

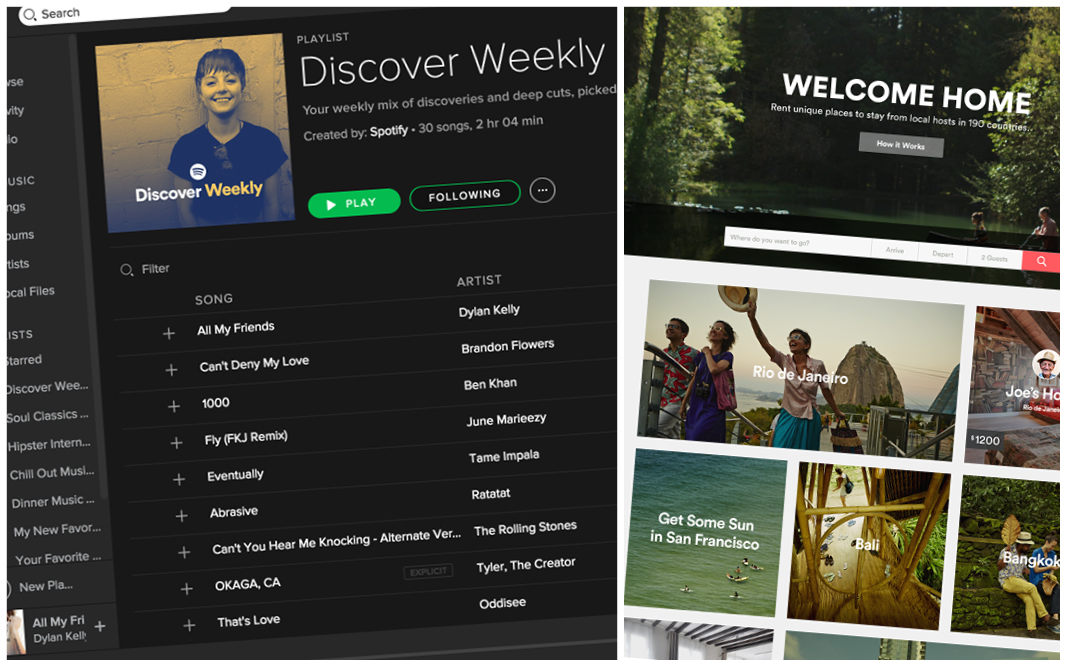

Providing a service through digital platforms such as Airbnb, and online activities such as providing blogs or open source content, offer different instances of new behaviour, not easily captured in current statistics.

In theory, the work involved and income made from renting out a spare room this way should be recorded, but might not be.

‘Volunteer’ digital services such as contributing to Wikipedia or open source software are not even counted in principle because they are conceptually similar to cooking at home or volunteering at school – these activities lie outside the ‘production boundary’ that defines Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Yet they are probably substituting for services people pay for, such as encyclopedias or proprietary software.

Other challenges are even trickier. In the digital sector all kinds of new activities and jobs are emerging, but these do not fit into the existing classification of sectors, which is heavily tilted towards manufacturing because its origins lie in the late 1930s. People select the classification they think suits their business best, so it is not obvious where newer industries such as video games or software development sit in the statistics.

It is harder to calculate price indices for some new services.

While the price of a CD was straightforward to measure, what is the price of a streaming service some people get for free (with advertisements) and others pay for, while some buy the same music as downloads or in physical form still?

What is the price of a recorded song or symphony, and is that the right kind of unit?

Another difficult question about prices – needed to calculate economic growth in real terms as well as the inflation rate – is whether they ought to reflect rapid improvements in quality.

A laptop bought today might be the same price as one bought three years ago but will have far better features such as speed, memory, screen resolution and so on.

Statisticians make adjustments to calculate quality-adjusted prices (or ‘hedonic prices’) for a few items; the question is whether they should cover more goods and services this way, or make the adjustments more comprehensive.

This is not an easy one to answer, as economists and statisticians have always understood that prices paid in the market never capture all the benefits people enjoy from their purchases.

Economists un-poetically call this extra value ‘consumer surplus’, but it refers to the longer life enabled by a new medicine, or the joy of being able to speak to a friend or relative far away. If statisticians start to make quality adjustments to prices that take them away from what the purchaser pays, where is the boundary between economic value and joy?

As if these were not enough, there are (at least) two other big challenges for statistics in the digital economy. Both stem from the way companies’ business models are changing. A growing number of businesses operate as digital ‘platforms’ offering low or zero prices to one set of consumers, subsidized by another set or by suppliers.

For instance, Google offers free search, maps, emails and so on, and is paid by advertisers. This makes it hard to define the value of any individual element of the service, or the price of the product.

What’s more, many of the large digital businesses operate globally, and will be headquartered overseas, and might also be registered for tax (and possibly statistical) purposes elsewhere. It is becoming increasingly difficult to trace the implications of the monetary transactions for the underlying economic categories including the balance of payments.

Internationally, statisticians are still in the early stages of recording and understanding the locational implications of global production and sales, especially for services.

"Internationally, statisticians are still in the early stages of recording and understanding the locational implications of global production and sales, especially for services"

The digital difficulties are not just a matter of academic interest. Official statistics are a vital source of information for the government in setting economic policies, and for the public in being able to hold politicians and officials to account.

Just as statisticians and economists in the early 20th century worked to define new measures and methods for the modern economy, their counterparts today will need to do the same for the digital, globalised economy.

Diane Coyle is a Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester and founder of the consultancy Enlightenment Economics.

She is a Fellow of the Office for National Statistics and member of the Natural Capital Committee.

She specialises in the economics of new technologies, markets and competition and public policy and has worked extensively on the impacts of mobile telephony in developing countries.

Her books include the bestselling GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History, The Economics of Enough: How to run the economy as if the future matters, and The Soulful Science (all Princeton University Press).

Diane was a BBC Trustee for over eight years, and was formerly a member of the Migration Advisory Committee and the Competition Commission.

She was previously Economics Editor of The Independent and also worked at the Treasury and in the private sector as an economist. She has a PhD from Harvard.

Diane was awarded the OBE in January 2009.

For more information on GDP, contact: gdp@ons.gov.uk

Other Visual.ONS articles

Why has the value of the pound been falling?

The gender pay gap - what is it and what affects it?

If you like our visual.ONS content and would like to see more, please sign up to our email alerts, selecting 'stories and infographics' under preferences.