A blanket ban of so-called ‘legal highs’ is due to come into effect this spring, following long-running concerns over how quickly they are being created and the potential harms they pose.

The Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 will outlaw the importation, production and supply of psychoactive substances, although alcohol, tobacco, caffeine and most medicines will be exempt.

What are ‘legal highs’?

‘Legal highs’ contain chemicals which produce similar psychoactive effects to ‘traditional’ illegal drugs like cocaine, cannabis and ecstasy.

There is no agreed official list of substances that are categorised as legal highs, but this article concentrates on the following types of substances:

• Stimulants like piperazines (eg BZP), cathinones (eg mephedrone), benzofurans and methiopropamine

• Sedatives such as benzodiazepine analogues (eg etizolam) and new synthetic opioids

• Hallucinogenic drugs like NBOMes and alpha-methyltryptamine

• Dissociatives, eg methoxetamine

• Synthetic cannabinoids such as 5FAKB-48

This article focuses on substances that were not controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 on the day the person died.

Concerns over ‘legal highs’

‘Legal highs’ first started to become more popular on the UK drugs scene in around 2008/09, with synthetic stimulants such as benzylpiperazine (BZP) and mephedrone, and synthetic cannabinoids such as Spice, among the first to gain popularity.

There has long been concern, since then, over deaths connected to ‘legal highs’ such as mephedrone; each fatality bringing with it an outcry for something to be done to prevent further tragedies.

The government has already banned a large number of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

However, it has been difficult to control the use of NPS with existing legislation, and the number on the market has increased rapidly in recent years.

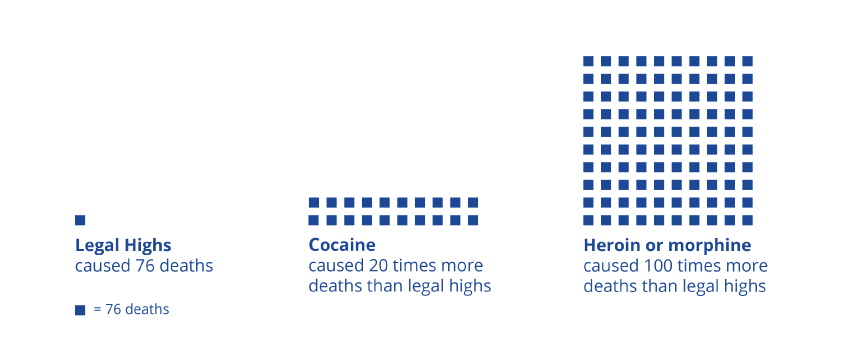

There were 76 deaths involving 'legal highs' (ie an NPS not controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act on the day the person died), in England and Wales between 2004 and 2013.

There has been a marked rise in the number of deaths connected to ‘legal highs’ between 2011 and 2013, when they more than tripled from seven to 23.

Five out of six legal high deaths are among men.

In 2013 alone, there were 23 deaths where ‘legal highs’ were a factor.

These trends should be interpreted with caution as they are based on very small numbers.

Number of deaths involving legal highs, England and Wales, 2004 to 2013

Embed code

Over the same period there were more than 100 times as many deaths involving heroin or morphine (7,748) and more than 20 times as many deaths involving cocaine (1,752).

Drug related deaths, England and Wales, 2004 to 2013

Most legal high deaths happen in people aged 20 to 29

The average (median) age for deaths involving a legal high is 28, which is younger than for drug misuse deaths, where the average age is 38. The youngest person to die from taking a legal high was aged 18 and between 2004 and 2013 only nine teenagers have died from this.

Little research has been carried out into the short or long-term harms of ‘legal highs’. So users are effectively acting as human guinea pigs, because they cannot be sure what substance they are actually taking, how much to take, or the effect it will have.

Around 60% of legal high deaths also involve another drug or alcohol

Embed code

More than half of all legal high deaths involved multiple drugs (57% on average between 2004 and 2013), but this proportion dropped to about a third in 2013. This could be a combination of legal highs and illegal drugs or a mixture of different legal highs.

Where more than one drug is mentioned it is impossible to tell which was primarily responsible for the death.

Street names for 'legal highs':

'Legal highs' cannot be labelled as being for human consumption, so are often marketed as plant food, bath salts, incense or research chemicals:

• Spice

• Clockwork Orange

• Bliss

• Ivory wave

Alcohol was involved in about 10% of legal high deaths between 2004 and 2013, though none of the 23 deaths in 2013 mentioned it.

Does banning a new psychoactive substance reduce deaths?

Mephedrone was one of the first legal highs to catch the media’s attention. Sometimes called ‘Meow meow’ or ‘M-Cat’ by the media, it is a cathinone substance which was controlled as a Class B substance under the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971) on April 16, 2010, along with a number of other cathinones.

But deaths involving mephedrone did not immediately fall after it was banned. In fact they continued to rise for several years afterwards, peaking at 22 deaths in 2012, before falling to 12 deaths in 2013.

Deaths involving mephedrone, England and Wales, 2009 to 2013

Embed code

Deaths involving mephedrone spiked between 2009 and 2012, despite evidence that mephedrone use was falling (Crime Survey for England and Wales). This could be down to people taking mephedrone in combination with other more dangerous substances, or using riskier methods to take it (eg injecting instead of snorting).

It’s also possible that prolonged use of the drug caused increasing harm, with escalating doses leading to more fatal overdoses; or it is possible that a more vulnerable group of people began using mephedrone. In addition, it may be that people stockpiled mephedrone before it was banned, which could have affected patterns of use after the ban.

There may be a complex relationship between a drug’s legal status, how widely it is used in the population and the number of deaths that occur.

Only time will tell if the blanket ban on NPS will affect the number of deaths associated with them.